The Benefits of Testing our Code: Introduction to Pytest

Table of Content

Writing Tests is One of the Best Habits We Can Adopt

Testing code might at first sound like something complicated that only trained software engineers understand. However I believe anyone can start writing them no matter the level of knowledge. This post aims to be a gentle introduction to testing. I’ll first highlight the benefits of using them and then show you how to write your first unit tests using concrete examples.

To begin let’s define what testing means. Very simply put testing means isolating a portion of our code, like a function, and verifying it works as intended. The most basic type of testing is called unit testing (it tests an individual unit of code) and a collection of unit tests is called a test suite. Unit testing is the type of test we will be discussing in this post as it’s the simplest to get started with. Unit tests typically run before code is pushed to a remote repository or once it reaches a certain environment and the test suite ultimately guarantees everything is ok and works as intended. If this sounds less scary than it initially was it’s because it is and I can’t stress this point enough: testing should be simple and help us understand what we created better, never the opposite. Before I introduce concrete examples of how to write tests using the pytest Python library, I’d like to highlight the benefits for us data scientists and BI analysts to write tests and why it’s a habit worth cultivating:

Checking our code actually works and does what’s its supposed to do. We have all been surprised by the behavior of our code at some point.

As important if not more than the first point: collaboration. Making sure my changes didn’t break the code my colleague implemented is important and vice versa. It implicitly increases the level of trust within a team knowing anyone’s changes are tested against the whole codebase.

Improve our understanding of how the code works and test against specific edge cases. Writing tests forces us to think about unexpected ways our code could behave and self-guard against it. For instance we want to make sure a function that only takes positive numbers as input is tested in the case it receives negative numbers and returns the right error message.

Simplicity. Testing a function or a class that performs one action, but do it well, is way easier than testing complicated chunks of spaghetti code. It usually becomes apparent when writing tests that our function is too complicated and should be simplified. Some even say tests should be written before the actual code.

Save time. A consequence of the above 3 points even though it might sound paradoxical as writing these tests takes a lot of time and effort at first. But on the long term it means less debugging, less back and forth between colleagues when a bug is introduced and a greater confidence in the codebase, making development more efficient.

Gain developers trust. This one is specific to our profession. Often software engineers don’t trust our code and don’t really want to get involved with it. This is our job to bridge the gap between data science and software engineering by producing quality code. The result is they will be more likely to support us once in production which is the only step that generates value. Failing to do so means our project is more likely to remain experimental and therefore of limited value.

Alright I hope by now I convinced you that writing tests is important. We are now going to write our first unit tests. Keep in mind this is an introductory post and we focus on unit testing, the “simplest” type of tests. However I strongly believe writing good unit tests add incredible value to our projects and makes us better data scientists. For further reading, start here.

Introducing the pytest Library

The pytest testing framework is great because it supports all kind of scenarios from basic unit tests to more complicated integration tests. It also comes with a lot of plugins and useful functionalities. Let’s see it in action.

Requirements

The only requirement here is to have Python installed on your machine. If that’s not the case, follow these instructions.

I will also use for my examples the Theseus Growth library. Theseus Growth is a great new project started by Eric Seufert that allows marketers to analyze their cohorts. It doesn’t include tests yet and makes for a perfect use case. I created a repository in my Github account that you can fork and use to follow the examples above.

Install pytest

Theseus Growth uses Poetry for dependencies management. I wrote a blog post about using pipenv to manage dependencies. Poetry is very similar to pipenv and I invite you to explore their project page to learn more. You can install the existing dependencies and pytest with the following commands in your terminal:

poetry install

poetry add --dev pytest

Here we tell Poetry that pytest is only used in development and not as part of the regular usage of the library by end users.

Create a Test Folder

You want to keep your test code separate from your project code to make things clearer. Navigate to the Theseus Growth folder on your computer and create a test folder.

cd path/to/theseus/project && mkdir test

Pick a Function to Test

If you navigate to the source code of Theseus Growth, there is a file called curve_functions.py. The file can be seen here as well. We are going to test the log_func function:

def log_func(x, a, b, c):

np.seterr(all='ignore')

return -a * np.log2(b + x) + c

The only thing we need to understand about this function for our example is that if we feed it a = 15, b = 3, x = 3 and c = 20 it’s supposed to return the beautiful number 58.77443751081734. So this is what we are going to test first.

Write our First Test

In the test folder we just created, create a file called test_curve_functions.py and enter the following code:

import pytest

from theseus_growth import curve_functions

def test_log_func():

a = -15

b = 3

c = 20

x = 3

assert curve_functions.log_func(x, a, b, c) == 58.77443751081734

Let’s understand what’s happening here. First we import pytest and the curve_functions module we want to test. Then you can see we create a function called test_log_func that will test the curve_functions.log_func we introduced above using a predefined set of parameters. Every test function should start with test as it’s how pytest automatically recognize a test function when invoked. Pretty neat right? Finally, the last line can be translated as follow: “Assert (verify) that the curve_functions log_func with this set of parameters is actually equal to 58.77443751081734 and not anything else.”

Run the Test

In a terminal from the project root folder simply call pytest in the Poetry shell like this (if you don’t know what a shell does, read here:

poetry run pytest # Yes it's that simple!

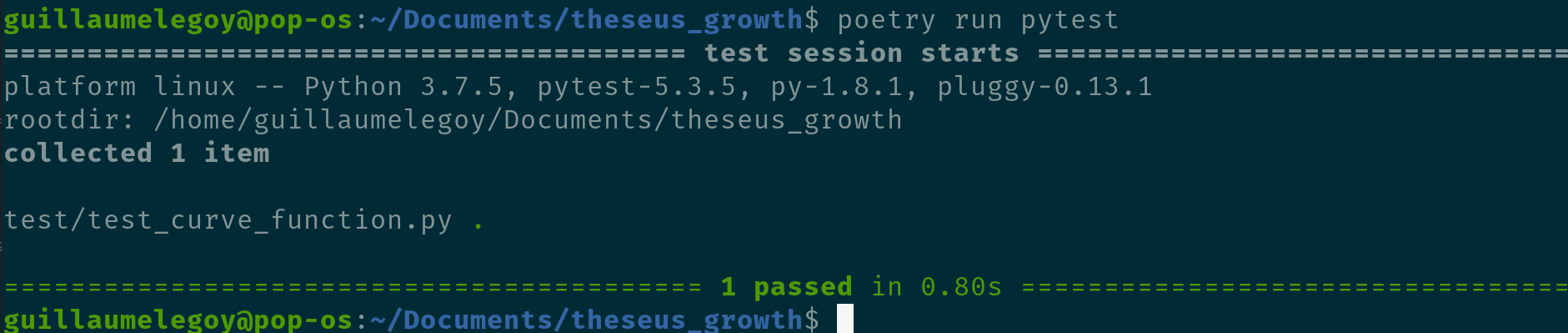

Pytest automatically found your test functions and ran your test. And this is the output:

Awesome it’s all green! However let’s quickly see what happens if you intentionally introduce the wrong value:

import pytest

from theseus_growth import curve_functions

def test_log_func():

a = -15

b = 3

c = 20

x = 3

assert curve_functions.log_func(x, a, b, c) == 999

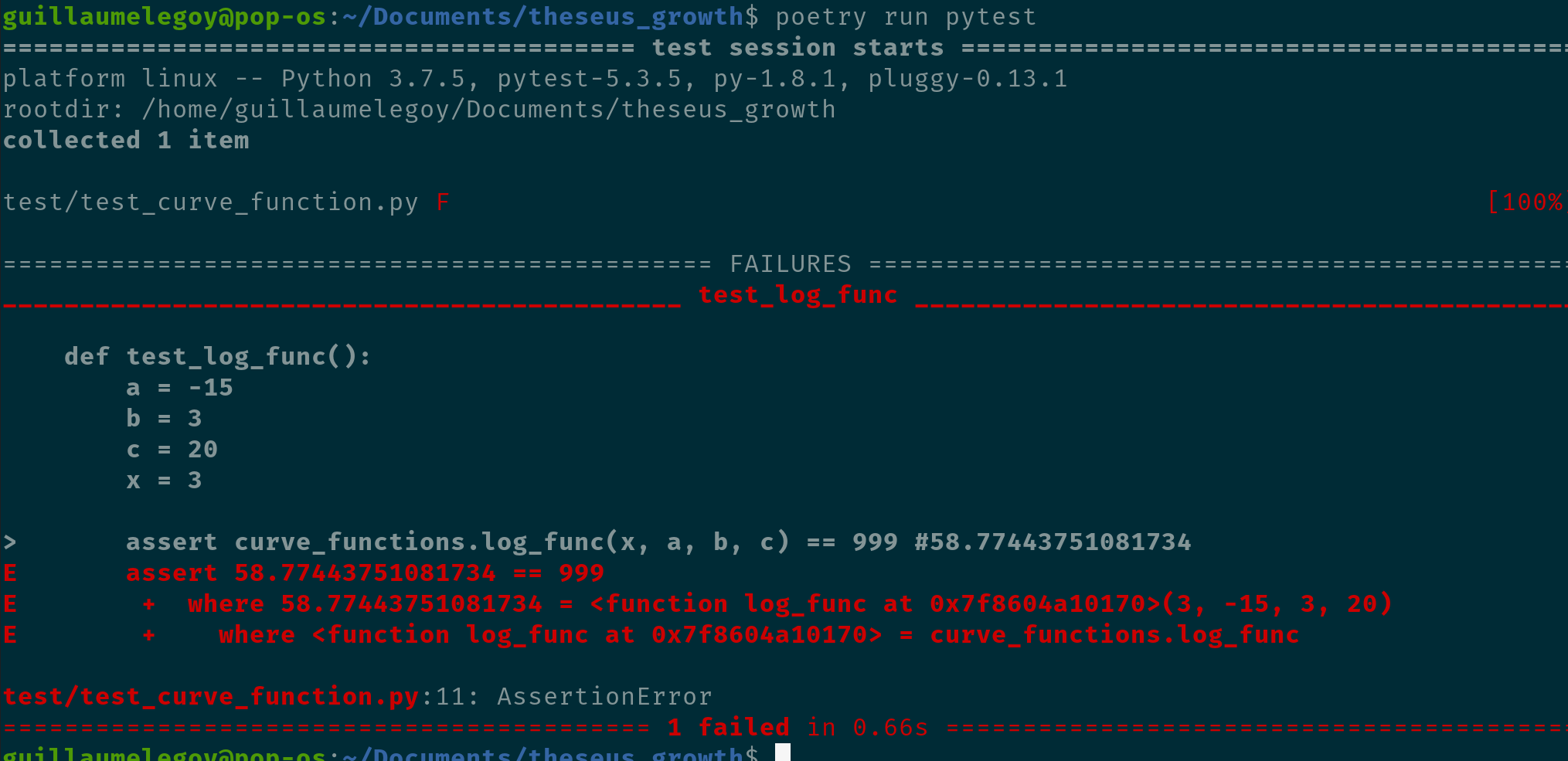

If you rerun the test this is what you see:

Pytest tells you exactly why your function didn’t pass by telling us that 58.77443751081734 was expected but we got 999.

That’s it we created our first test. This means that from now on, anyone modifying this log_func can do so with peace of mind as running the tests afterwards will tell them if they actually broke something or not. As mentioned in the introduction, this is a great way to enhance collaboration and make our code more robust!

Another test we could create for the same function is to verify that any b + x value equal or less than 0 returns an error message. Indeed this function can’t take negative values or 0. The error message should warn the user that they are trying to do something not mathematically sound. However you already noticed that no such message is present in the original log_func and therefore should implemented. This is another benefit of testing: improving our understanding of how our code behaves and make sure that edge cases or unintended usage of our code is covered and taken into account.

Going Further: pytest Fixtures and conftest.py

Even though you can already get started and write basic tests, I want to introduce the concept of fixture offered by pytest. Very simply put fixtures are functions that get injected into test functions as arguments. Fixtures are incredibly powerful because they can be used by any test function independently, meaning using one fixture function in one test function doesn’t modify its behavior if used in another function. This is important because tests must be independent from each others in order to be reliable.

Using our example above, a fixture could be created as follow:

import pytest

from theseus_growth import curve_functions

@pytest.fixture

def example_fixture_x():

x = 3

return x

def test_log_func(example_fixture_x):

a = -15

b = 3

c = 20

assert curve_functions.log_func(example_fixture_x, a, b, c) == 58.77443751081734

This example is a bit contrived and you probably wouldn’t use it as is, but the goal here is to make you understand what a fixture does, as I personally had some trouble with the concept initially. Here you can see we define a fixture by using the pytest.fixture decorator on top of the example_fixture_x function that simply returns 3. We can now use this fixture we just created in the test_log_func as an argument that basically replaces the x variable in the previous examples. This same fixture could be used in any other test function we create.

Last neat trick: let’s say you have multiple test functions scattered across multiple scripts in your test folder, all using the same fixture function. Rather than copy pasting this fixture in every script, you can create a conftest.py file and put your fixture in it. Pytest will automatically detect it if used in any test function.

That’s it for this introduction to testing. We barely scratched the surface and you can expect more blog posts covering the subject coming soon. However you can already get started and accomplish a lot just with what we covered and the help of the online documentation of the pytest library.

Happy coding!